I was saying to a friend that it is a challenge to my understanding of the dharma to teach dharma to kids. I may have an experiential understanding, or I may have some big-words understanding, but I must study and delve some more so that I can relate it so a kid can understand. My band of girls is not shy about asking the meaning of words, so I don't worry too much about that, but I do worry that I may misrepresent the dharma.

So I cast out a net to find out how other people understand it. With the paramitas, I always remember my friend Yuishin saying that the song says it all. In this case, "Now the sixth paramita is Prajna/ If you think you're wise, you're full of bologna/ But when you experience "I DON'T KNOW"/ then natural wisdom is everywhere you go." When it comes to Zen, this is a strong message of Prajna. Casting my net, I found this is a beloved topic of Tibetan Buddhists.

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche said, "This prajna of mindfulness is divided into a three-stage process of development in the path of Buddhism. We have the prajna of listening, the prajna of contemplating, and the prajna of meditation." I didn't realize that when I mentioned, "Tibetan Buddhists" the girls would be reminded of familiar images they've encountered and want to mention them. (Monks who visited one girl's school; that Holiness Dalai guy?) I must remember for future lessons that any little tangential fact might just spark a tangential conversation. Not that there's anything wrong with that...I love it when they're bursting to tell about the things they know...I just need to plan how much I can cover in a lesson.

Judy Lief, teacher and author who studied with Trungpa, said,

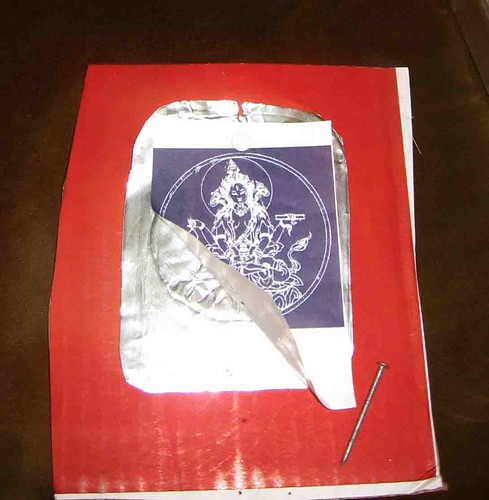

"Prajnaparamita is depicted as a beautiful feminine deity with four arms. Two arms are folded on her lap in the classic posture of meditation, and her two other arms hold a sword and a book. Through these gestures, she manifests three aspects of prajna: academic knowledge, cutting through deception, and direct perception of emptiness."

(Here is an image of Prajnaparamita, known as the Mother of the Buddhas.)

Through these three aspects and the connection to the Prajnaparamita Buddha, I had a way into the lesson. I asked the girls to listen for these three kinds of Prajna as I told them the story.

This story is based on Jataka #305. I used Sarah Conover's version in "Kindness: A Treasury of Buddhist Wisdom for Children," changing the characters to girls, and adding a post-climactic ending that helped the story reflect the three stages of Prajna.

Steal for Teacher?

Once upon a time there was a school for girls who wished to lead a spiritual life. It was a small school, and the girls had a wise old teacher who taught them the usual subjects like History and Math and Reading, but she also taught them how to behave and how to understand the world. What are some of the things you think she taught the girls?

(The girls had some good answers. How to be peaceful. How to behave in the world. Breathe! How to meditate. etc...)

So one day this teacher gathered the girls together and told them she was getting old. Could they not see she had grey hair and needed to use a cane? Well, she was finding it more difficult to earn the money to support the school, so she needed their help. "I need you to help find money to keep the school open," she said.

The girls wanted to help. One girl asked, "How can we get money? We only know how to do our chores?"

The teacher told them, "There are riches everywhere you look. When you see a man with a shiny watch and rich suit walking down the street, don't you think he has more than he needs? It wouldn't hurt him to share some with us, don't you think?" The girls looked at each other, nervous and confused.

"Here's what you do," the wise old teacher said. "Go to the city center and find a quiet alley between busy streets. When someone walks by who clearly has a lot of money, with no one watching, I want you to take his wallet, or her purse, or other valuable things. If no one has seen you, I will accept what you bring. We will use the money to pay our bills, and sell other valuables. But if you let yourselves be seen, I will refuse any item, even if it is a diamond ring."

The girls were concerned and frightened at their teacher's request. Wasn't it wrong to take other people's things? They looked at the floor and avoided each other's eyes. "Remember," the teacher said, "I wouldn't ask you to do something I myself wouldn't do. You know I have always told you the truth. Our school could certainly use the money."

As she spoke, the teacher guided the girls to the door. "Return soon," she said. "You will find it very easy when no one is watching." The group gathered shoes and coats, buzzing with some fear, some excitement. When the door closed behind them, there stood a single, quiet girl.

The teacher noticed and approached her. "What is the matter? All the other girls are brave and willing to help me keep the school open. Why didn't you join them?" The voice was soft but with a little bit of a challenge.

The girl looked at the floor, whispered, "Teacher, I cannot do what you asked us to do."

"Oh. Why is that?" The gruffness in her voice disappeared, and the teacher watched the girl with a soft concentrated eye.

"Because there is no secret place where no one watches," answered the girl. "Even if I'm by myself, I will see myself steal."

Hearing this response, the wise teacher hugged the girl joyfully. "Congratulations! Good for you! You understood my true meaning, you really listened to me. I am proud of you!"

The girl's face lit up. "Thank you, teacher!"

Right then the other students came back for the missing girl, and they realized their teacher had tested them, and they were humbled. It was an important lesson for them to learn. First they studied, they listened and they learned. But then they needed to take what they learned and make it their own. They never forgot the girl's words, "Wherever I am, someone watches." They never forgot how important it is to pay attention to one's own understanding and own conscience.

This was not the end of their learning though. That girl eventually became a wise teacher herself. Her understanding became truly wise when she no longer needed to remember 'the one who watches.' She no longer felt separated from that one. When she meditated, when she listened, or spoke, or did something, she did not plan or tick required actions off a list. Rather than having all the answers, she approached each moment as a question, and thus she almost always found the wise response.

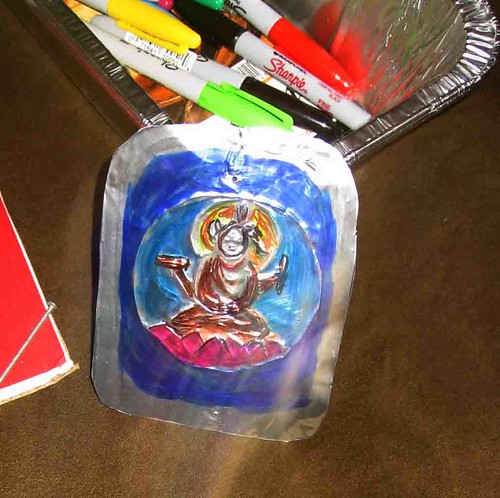

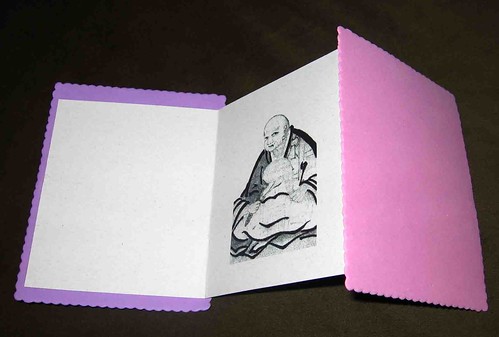

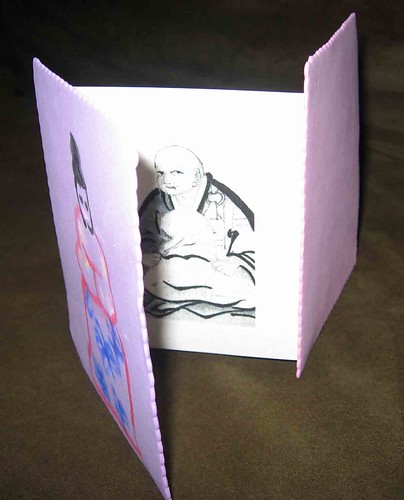

We made aluminum ornaments for the activity.

Use thumbtacks to hold the aluminum (pie tin, roasting pan, or in this case with an unstamped bottom, large loaf pan) to the cardboard, and the imaged to be traced if one is being used. Use a nail to make impressions in the aluminum. Once enough is traced, the nail can be used for further details and molding.

Conversation: "The nail is tearing the paper!"

"Yes, that happens."

"That's how you know you've traced that part!"

Some girls opted to draw their own images.

In my case, I turned the tin over and colored the back, but it didn't matter which side they chose to give color.